Five Keys to an Effective Training Needs Assessment

The task of conducting a training needs assessment can be both a moving target and an ambiguous one. Here’s a deep dive into the topic, organized into five primary stages:

- Uncover the financial justification for training

- Define the Path to Optimal Performance (POP) for your learners

- Identify obstacles to achieving the POP

- Sketch out a 70:20:10 Learning Program

- Apply established estimating methods

1. Uncover the Financial Justification for Training

For some reason, many guides to training needs analyses obscure the financial justification, or tuck it in as an afterthought, calling it simply the training need, or business case, or training objective. This is dangerous.

Why is the financial justification for training so important?

Simply put, because your company’s reason for being is money, and money gets attention from your company’s senior leaders. Without an understanding of your training program’s financial benefits – and risks – you are seriously limiting your ability to build the right program for the job. The only thing worse than not having enough funding to create effective training, is to find yourself defending a program that clearly costs more money than it could possibly return to the organization.

But what if your internal client doesn’t have a well-defined financial justification?

You’re certainly not alone. Only a small minority of stakeholders seem to give much serious thought to quantifying – in financial terms – the potential impact of their requested training.

To be clear, you do not need a full-blown cost-benefit or ROI analysis to start scoping your project. However, you should at least know how many zeroes are in the potential financial return (or savings) to the organization, to be sure your budget seems realistic.

How Do I Uncover Financial Drivers?

Time to play doctor. Remember the last time you had a checkup? You may have been asked to briefly describe the reason for visiting, but then the doctor immediately began asking questions and gathering data.

Take a page from the doctor’s playbook and treat your internal client a bit like a patient. This way, you take control of the conversation and come away with more useful information than if you let the client control the dialogue. Your approach should be closer to the appreciative inquiry method than that of Gregory House, M.D. – positive, curious, and above all, collaborative.

In the doctor’s office, the questions are numerous, detailed, and well-organized. Many questions are not open-ended. Your doctor doesn’t want you interpreting your situation any way you want. Your health is too important, and complex, to let your personal hypotheses cloud the picture.

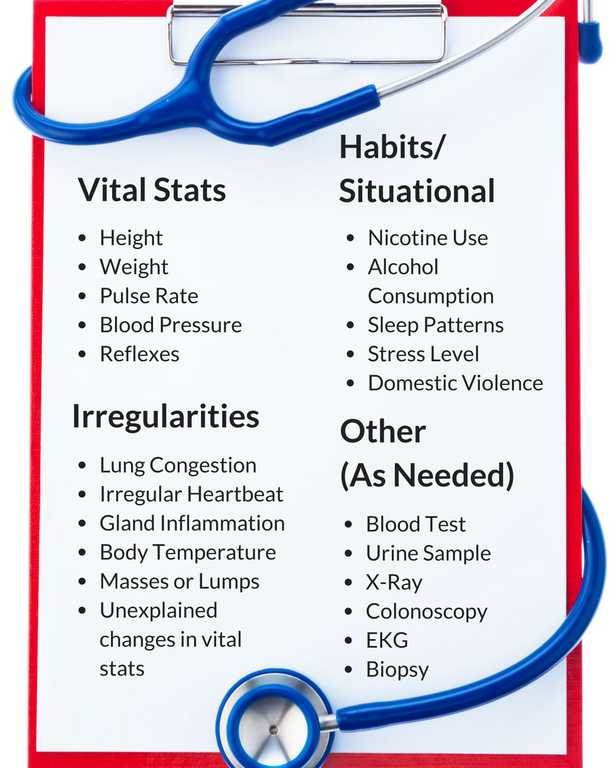

Here is a sampling of the type of data gathered by your doctor:

The doctor doesn’t just ask what you hope to accomplish by visiting. She asks a whole lot of questions before you even know what’s hit you.

Many L&D people reading this may already use a checklist of questions, which is awesome. We’ve seen a lot of those checklists over the years, and many ask one or two business-related questions, then transition straight to eLearning seat time and SME availability.

Here is the data you should be ready to gather when your internal stakeholder starts talking about a training need.

This data will help uncover financial drivers, not just learning objectives. Almost all of these data points have a financial implication. For example:

- A high turnover rate means unnecessarily large amounts of money spent on:

- Recruiting and onboarding new hires

- Training new hires

- Fixing errors and performing re-work due to a perpetually “green” workforce

- Performance irregularities like a spike in customer satisfaction issues cost money by requiring:

- Additional staff to compensate for process or performance breakdowns

- Time and attention from senior managers to troubleshoot issues

- Dismissal and replacement of problem employees

The point is not to arrive at a specific dollar amount. Your stakeholder won’t have patience for that level of analysis, and frankly, may not be too excited to have specific figures floating around about lost revenue and preventable expenses.

The idea is not to let your client off the hook with one or two simple statements about why training is necessary.

2. Define the Path to Optimal Performance (POP) For Your Learners (Beware of Learning Kryptonite!)

Now that you know how much money is at stake, it’s time to figure out how to make an impact. Without a financial business case, you won’t have a good way to push back when your stakeholder starts throwing around Learning Kryptonite.

What the heck is Learning Kryptonite?

Learning Kryptonite is the use of words that have the same effect on learning projects that Kryptonite has on Superman: complete debilitation. Kryptonite Words are those that – if allowed to steer your training project – could doom it to mediocrity, or even outright failure.

Examples of Learning Kryptonite Words:

EXPLAIN, LEARN, REMEMBER, APPRECIATE, UNDERSTAND

These objectives aren’t inherently bad. But for a training project to be successful, they simply aren’t sufficient. They become outright dangerous when not at least accompanied with action words – verbs that indicate what learners need to do following training that puts them on a Path to Optimal Performance (POP). Here are words and objectives you should be looking for:

PERFORM, EXECUTE, DO, DEMONSTRATE, MODEL, ACT

The point is simple – stakeholders offer objectives like:

- “I need everyone to remember the product features of our new blood analysis device.”

- “Our people have to understand the new FDA regulations.”

- “Everyone should appreciate the importance of customer satisfaction.”

The trouble with these objectives – all laden with Learning Kryptonite – is that they will likely result in “scrap learning.” My colleague Andrea May describes this concept in How to Avoid Scrap Learning:

Scrap learning is learning that is delivered but not applied back on the job. According to a recent white paper titled Confronting Scrap Learning by CEB Global, “For the average organization, 45% of learning investments are scrap learning.” In a world where we all have to do more with shrinking budgets and resources, that is a shocking amount of waste.

It’s not enough to create and reinforce engaging training. Training must result in sustained behavior changes that actually help deliver a financial return to the organization.

To articulate your objective then, without using Kryptonite Words, you’ll want to clearly describe the specific set of actions that lead to success, or the Path to Optimal Performance (POP). For example:

- Demonstrate effective listening, observation, and communication techniques

- Create a successful business plan using the 4-step process involving production goal setting….etc.

- Replace valves and fittings in DOT IM tanks

- Modify the ClinCheck Treatment Plan and submit changes to it

- Use the Six-Step Paradigm to diagnose an acid-base disorder

Learning Kryptonite objectives define what we want learners to know. The POP approach details what we want learners to do.

3. Identify the Obstacles to Achieving the POP

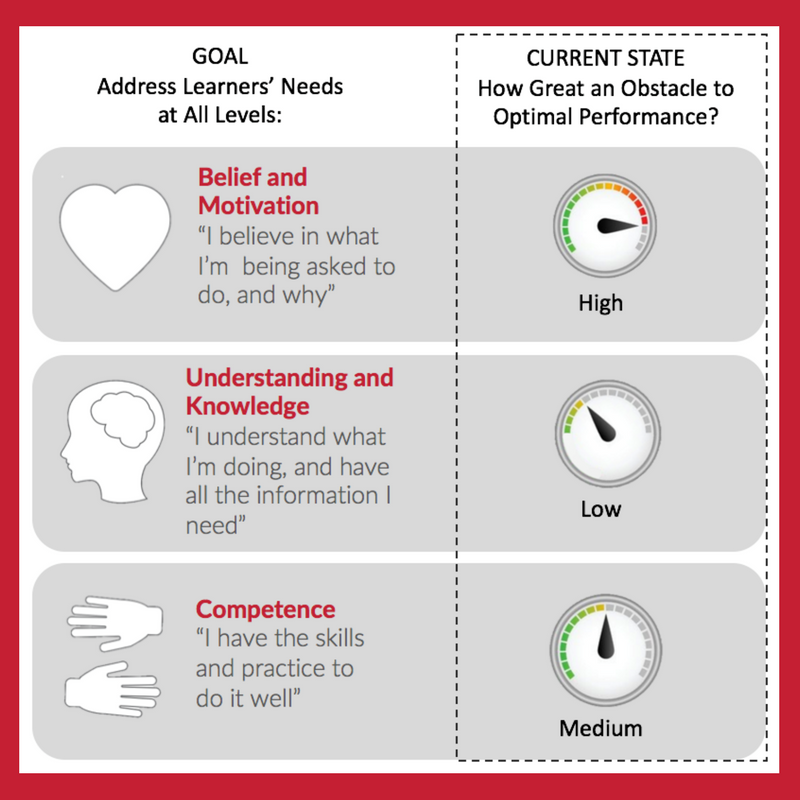

Obstacles on the Path to Optimal Performance are not all created equal. Some are easy to spot, while others are invisible, with the potential to undermine your training and leave you wondering what happened. To systematically uncover these issues, we group them into three categories: Head, Heart, and Hands. The goal is to foster Belief, Understanding, and Competence.

If your client says, “sales reps don’t understand the new pricing model for our diagnostic equipment,” – that’s an Understanding barrier. Dig deeper. As discussed earlier, if all you get is a list of things learners “don’t know,” that’s classic Learning Kryptonite.

Understanding is only one element of what drives performance. We still need to know more about the learners’ Beliefs and Competencies.

To discover Beliefs and Competencies, you might ask:

- Has your department done an employee engagement survey lately? What were the results?

- Are sales reps satisfied with their compensation and commission plans?

- Were sales reps involved in creating the new pricing model? Are they happy with it?

Ideally, conduct a series of interviews and/or survey learners and their managers to better understand the Beliefs and Competencies present in the workforce.

Eventually, you’ll compile a scorecard of sorts that summarizes the degree to which each need presents barriers to Optimal Performance. It might look something like this:

In the above example, training may end up playing only a small role in the final solution, since the greatest obstacle is motivation (Heart). Knowledge and skills (Head and Hands) are only modest barriers to success.

In cases like this, asking learners to consume too much formal eLearning, or sit through an instructor-led course, could actually make matters worse.

In Nuts and Bolts: When Training Works by Jane Bozarth, she questions the ADDIE method for its presumption that training is required even before the performance problem is fully understood. Bozarth writes:

“Many trainers and designers employing ADDIE begin with the assumption that there is a training problem, so they move right into analyzing the specifics, and then they design and deliver the instruction. There are lots of tools to support practitioners in the analysis phase, from skills checklists to task analyses. Few lead to asking, though, whether training is indicated at all.”

Once you have a good picture of likely obstacles on the Path to Optimal Performance, it’s time to start planning the training you will – or won’t – produce.

4. Sketch Out a 70:20:10 Learning Program

Honestly, deciding what learning modes to use for your program deserves (at least) another blog post. For now, we recommend that you make an effort to build as little formal learning content as possible. Most programs involve at least 20% too much seat-time – with the excess focused on, yep, Learning Kryptonite (know this, understand that, and remember the other thing).

Instead, create a blended learning program that leverages the 70:20:10 principle to reduce formal learning time.

As a reminder, the 70:20:10 Blended Learning Model states that 70% of adult learning takes place by doing, or while on the job; 20% happens by working with others, and only 10% takes place as the result of formal learning interventions like eLearning and instructor-led training.

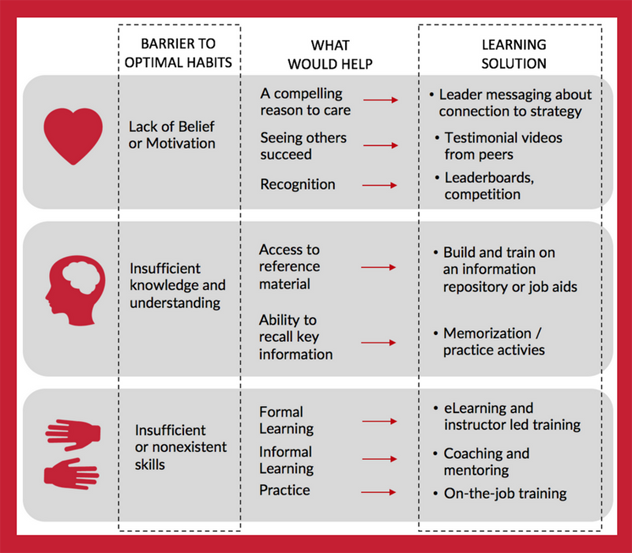

Here’s what a blended learning program that addresses all levels of learner engagement (Head, Heart, and Hands) might look like:

Using this method, you can naturally reduce formal learning seat-time by:

- Delivering “Heart” messages (why this is important, how it fits with our strategy, etc.) with short videos of senior leaders or testimonials from peers. Make these videos available before rolling out eLearning and classroom content.

- Focusing eLearning on “Head” messages (g., high-level overviews of process changes), along with an introduction to “Hands” material.

- Restricting classroom content to “Hands” content (here’s how to perform the new tasks). Classroom sessions should focus on the 20% of material that is likely to cause 80% of the questions. This frees up ILT time for what it’s best at: role-plays, scenarios, and immediate feedback.

- Creating simple coaching guides for managers to review new skills and behaviors with learners once they’re back on the job.

- Placing everything else (reference material, product knowledge details, detailed instructions) in an online repository learners can access on the job.

5. Apply Established Estimating Methods

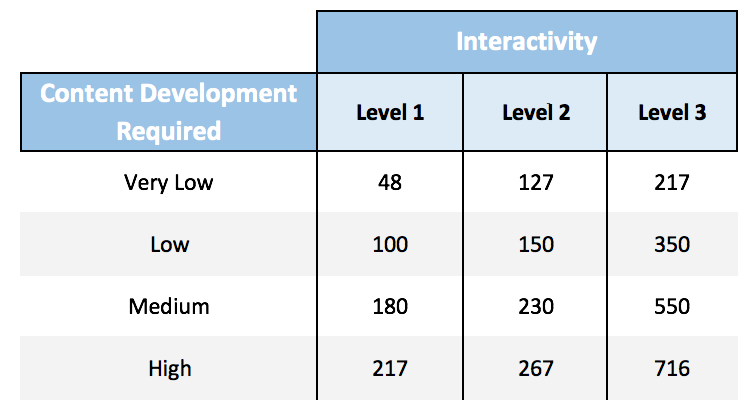

While using development ratios to estimate learning development time isn’t always perfect, these ratios provide a good starting point if you just need to understand “how many zeroes” are in the cost.

You can’t always trust your stakeholder to accurately assess how easily content can be converted to learning experiences. For example, you may be presented with a set of PowerPoint presentations and told,

“Here’s the material, please convert it into a set of engaging eLearning modules.”

Upon closer inspection, you discover gaps in the material, inconsistencies in process documentation, and no organizational or business context.

To address this problem and make estimating easier, we’ve augmented interactivity-based development ratios with a “content readiness” component. This provides a matrix of development estimates, not just a series. It looks something like this:

Development Hours Required to Produce One Hour of eLearning

The ratios vary depending on the degree to which the content is “ready for prime time.” Obviously, highly interactive eLearning modules with simulations and scenarios take longer to develop than basic page-turners.

In Conclusion

In truth, we just scratched the surface of scoping learning engagements, but hopefully you found an idea or two that can help in your work.

Continue reading

Dashe joins ttcInnovations

Learn More

Embracing the Future: Early Adopters of Generative AI for Learning

Learn More

Four Areas To Consider When Designing Accessible Training

Learn MoreCommitted to

finding solutions